Medicaid and Continuity of Coverage for the Justice-Involved Population:

An Assessment of Select Michigan Counties and Jails

- Report Navigation

- Overview

- Jail Versus Prisons

- Medicaid and Jails: The Basics

- Eligibility

- Coverage During Incarceration

- Suspension versus Termination

- Challenges with Care in Jail Settings

- Care Delivery

- Pre-Trial Detainees

- Policy Changes

- Sequential Intercept Model

- Research Methods

- Interview Methods

- Barriers Experienced by Interviewees

- Inconsistent Suspension Status

- Difficult Reactivation Process

- Ineffective Partnerships

- Lack of Resources

- Unpredictable Release Dates and Times

- Identified Innovations

- Comprehensive Screening for Medicaid Status/Activation

- Standard Discharge Protocol

- Collaboration Between Partners

- Use of Peers

- Recommendations

- Considerations for Recommendations

- Conclusion

- References

- Footnotes

- Overview

Overview

It has been widely reported that Medicaid coverage of the justice-involved population positively impacts health outcomes and reduces recidivism (Plotkin & Blanford, 2017). Federal law requires counties to provide health care to people housed in jails, however, Medicaid funds may not be used to cover services provided to an incarcerated individual.

Despite the Federal requirement and without comprehensive Medicaid screenings, continuity in health care coverage for released individuals is often overlooked. Only 28% of jails nationwide are screening for Medicaid eligibility to ensure post-release care coverage (Plotkin & Blanford, 2017). This continuity is critical as Medicaid eligibility expands the universe of services an individual leaving jail can access (i.e. mental health, substance use disorder treatment, case management, and physical health care).

Once released, individuals often face barriers to accessing health care services, which contribute to recidivism, drug use, and poor and costly health outcomes (Gates et al., 2014). The lack of eligibility screening, disrupted continuity of health care coverage, and bleak health outcomes for the justice involved population point to the need for Michigan's health care leaders to prioritize this issue.

The Wayne State Center for Behavioral Health and Justice (CBHJ) contracted with TBD Solutions in June of 2020 to conduct a focused study of current Medicaid enrollment and reactivation processes with the currently or previously incarcerated population. The purpose of this report is to inform Michigan's efforts to strengthen Medicaid enrollment practices for the justice-involved population by developing and enforcing consistent policy. Specifically, this report:

- Identifies and documents current practice, including barriers and examples of innovation, in select Michigan jails by interviewing jail and Community Mental Health (CMH) staff

- Summarizes best practices from other states that were gleaned through national research

- Outlines recommendations to improve access to necessary Medicaid services for individuals recently released from jail1

- Provides potential funding and cost saving opportunities for state-wide and jail-level Medicaid activities

Jail versus Prisons

The Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) oversees health care provided to individuals housed in state prisons. County jails are managed by their respective counties, and as such, there is no overarching authority over all jails in the state. Due to the complexities and differences between jail and prison related to Medicaid enrollment, and health care, this report only discusses the experiences of individuals and administrators in select Michigan jails. Although individuals released from prison may experience similar or additional barriers to accessing health care or Medicaid, the plight of those previously or currently incarcerated in state or federal prisons is outside of the scope of this report.

Medicaid and Jails: The Basics

Eligibility

Medicaid is a federal- and state-funded benefit plan available to low-income individuals, eligible pregnant women, children, and individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income (CMS, 2020). With Medicaid, individuals can access important services such as doctor visits, mental health services, substance use disorder treatment, prenatal and maternity care, medications, and preventive care services. As of March 2020, Medicaid provided coverage to 2,300,000 individuals in Michigan (Norris, 2020). With the Affordable Care Act's Medicaid Expansion opportunity, Michigan's plan (named Healthy Michigan) expanded coverage to an additional 650,000 people in early 2020 (Norris, 2020). The Healthy Michigan Plan expanded the number of incarcerated individuals eligible for Medicaid, which increased the urgency and importance of clarifying jail Medicaid enrollment and eligibility practices.

Incarceration does not impact an individual's eligibility for Medicaid enrollment.

Per the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), "if an individual meets all applicable eligibility requirements the state must enroll or renew the enrollment of the individual effective before, during, and after the period of time in the correctional facility."

(SOH 16-007)

Coverage During Incarceration

The Medicaid Inmate Payment Exclusion Policy forbids Medicaid reimbursement for services provided in jails (MAC Learning Collaboratives 2017). The only exception is care delivered outside the institution, such as at a hospital or nursing home, when the person is admitted for 24 hours or more (Dickinson, 2016).

Without coverage for care provided while incarcerated, counties bear responsibility for the cost of health care for incarcerated individuals housed in their jails (Chase et al., 2019).

Suspension versus Termination

Because most care is not covered by Medicaid during incarceration, states are left to decide how they will "deactivate" and "reactivate" Medicaid coverage for individuals currently incarcerated. In 16 states, including Michigan, Medicaid eligibility is suspended, not terminated, when an individual is incarcerated. This, ideally, allows coverage of Medicaid services to resume immediately upon re-entry into the community.

Once an individual re-enters their community, it is critical for their Medicaid Program Enrollment Type Code (PET Code) to no longer indicate their incarcerated status via a "INC" indication. If the PET Code wrongly indicates incarceration status, Medicaid coverage is interrupted.

For the sake of this research summary, the terms "Medicaid Suspension" or "Medicaid Suspension Status" are referring to individuals having the INC PET Code assigned to their Medicaid information. (Dickinson, 2016).

Challenges with Care in Jail Settings

Care Delivery

Jails admit 18 times more individuals than state or federal prisons, and these individuals stay a relatively short time (26 days or less) (Chase et al., 2019; Zeng, 2019). Given the ever-changing environment and short lengths of stay, jails are forced to focus on short-term solutions to potentially chronic and unmanaged health care concerns.

Pre-Trial Detainees

Unlike prison, jails house both sentenced individuals and unsentenced individuals. Sixty-five percent of local jail inmates are pretrial and are still presumed innocent. These individuals cannot receive most Medicaid services while in jail awaiting trial. Those who receive a public recognizance bond, in contrast, can enroll and participate in Medicaid covered services in the community.

Meet Frank: A Case Example

Frank was recently arrested for attempted robbery and is awaiting trial and presumed innocent. His insufficient savings made "bonding out" impossible, Frank must remain in jail while he awaits his trial. Frank's friend, Jack, was also arrested for attempted robbery in the same incident. He was able to post bail and is now back to working and living in his community.

Jack can access his Medicaid and seek care from his primary care physician. Frank cannot access his Medicaid coverage for health care needs while he is in jail. When he leaves jail, he will likely wait days or weeks for his Medicaid to be reactivated. Even if he was proven innocent, Frank's essential health care coverage was interrupted.

Policy Challenges

Michigan has no clear policy regarding the role nor the process for county jails to use in determining eligibility or enrolling eligible jail residents in Medicaid. This lack of statewide policy or guidance creates an inconsistent, fragmented, and inequitable system for individuals incarcerated in jail. Timeliness to enrollment and Medicaid reactivation varies from county to county creating access disparities depending on an individual's location of incarceration.

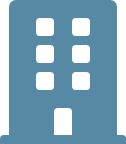

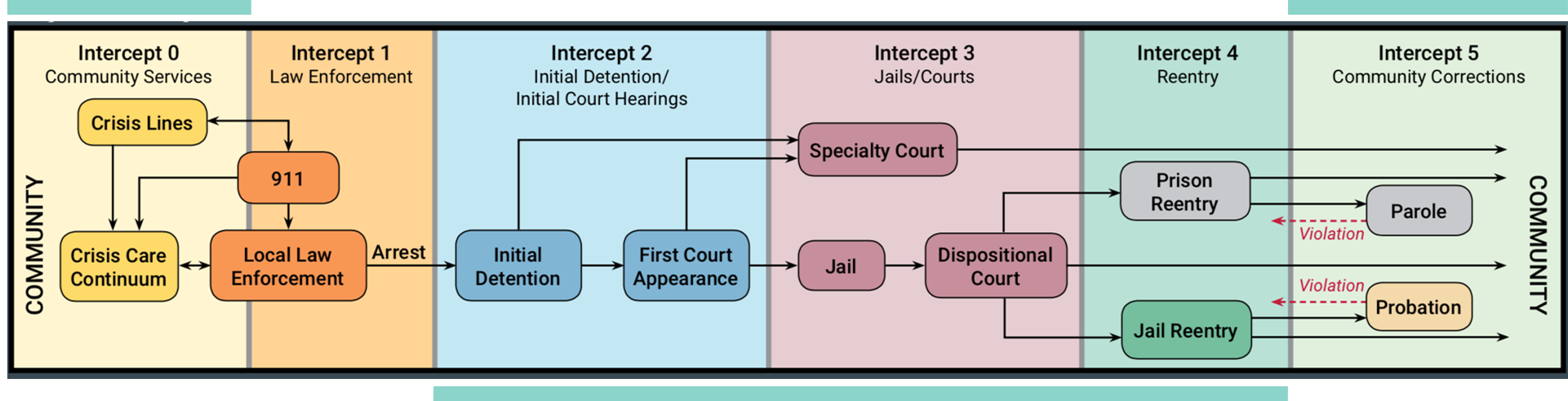

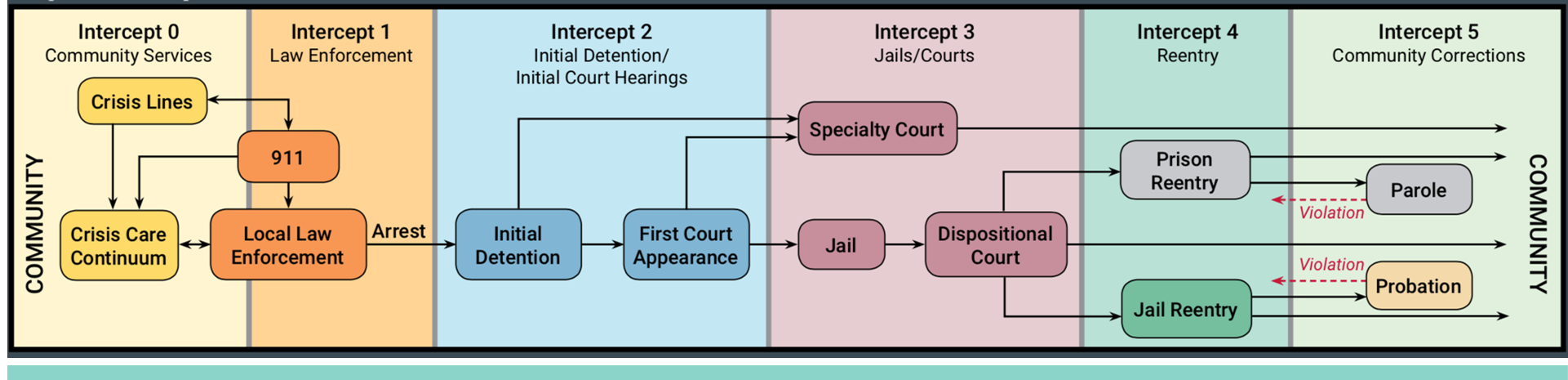

Sequential Intercept Model

The Sequential Intercept Model is a framework developed to map the locations (or intercepts) in which an individual interacts with the criminal justice system. To best tackle the needs of individuals currently, previously, or at risk for involvement in the criminal justice system, solutions at each intercept must be considered. Specifically, Medicaid enrollment and reactivation must be considered at every intercept in the model to ensure comprehensive coverage and continuity. This report will reference intercepts on the Sequential Intercept Model and utilize its framework to describe or propose solutions.

For more information about the Sequential Intercept Model and its uses, visit the www.SAMHSA.gov website or the Urban Institute (Willison et al., 2018).

Research Methods

To better understand the barriers faced by jails and community partners, TBD Solutions conducted interviews with subject matter experts in select county jails and CMHs. Between August and September 2020, 34 individuals were interviewed in 14 interview sessions.

Interviewee Selection Criteria: Interviewees for this study were selected based on their existing relationships with the Center for Behavioral Health and Justice (CBHJ), their job titles and responsibilities, and their rural-urban classifications as defined by the Michigan Department of Corrections.

Interviewee Selection Criteria: Interviewees for this study were selected based on their existing relationships with the Center for Behavioral Health and Justice (CBHJ), their job titles and responsibilities, and their rural-urban classifications as defined by the Michigan Department of Corrections.

Interviewee Regional Representation: Interviewees represented 12 Michigan counties, including Barry, Eaton, Jackson, Iosco, Kent, Marquette, Monroe, Muskegon, Oscoda, Ogemaw, Washtenaw, and Wayne counties. Representatives from Ogemaw, Iosco, and Oscoda counties were interviewed in one group interview. Interviewees from the three counties reported their barriers and innovations collectively. Subsequently, these three counties are considered one "jurisdiction."

Interviewee Job Titles: The job titles of interviewees included, Sheriffs and other jail administrators, CMH employees providing in-jail and community services, jail nurses employed by third-party providers, and in-jail clinicians employed by third-party behavioral health providers.

The experience of Michigan's Department of Health and Human Service (MDHHS) field staff are critical to fully understand the scope of Medicaid enrollment and reactivation. However, MDHHS field office workers were not included in the scope of this project.

To ensure confidentiality of participant responses, the counties of interviewees are de-identified within the results of this report.

Interview Methods

Background information provided by the CBHJ and results from the Jail Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) Survey2 were used to develop specific questions, reduce duplication of research efforts, and ensure the interviewers had useful contextual information to guide this effort. Two TBD Solutions employees conducted and summarized interviews.

Barriers Experienced by Interviewees

Interviewees reported significant barriers both reactivating individuals' Medicaid and engaging comprehensive enrollment activities for non-enrolled individuals. The four main barriers that caused disconnected care for individuals returning to the community were:

- Inconsistent suspension status

- Ineffective partnerships

- Lack of resources

- Unpredictable release dates.

All interviewees experienced more than one barrier, where each barrier often exacerbated another. These challenges led to disrupted care, long wait times for key services, unfilled or delayed access to essential medications, and lapsed or terminated health care access for an already vulnerable population.

Inconsistent Suspension Status

No pattern or correlation was identified between which jailed individuals were placed in suspension status and which were not. Some individuals left after a 6-month incarceration with full active Medicaid, while others stayed a short time, and their Medicaid was suspended.

Despite Michigan being a suspension state, one interviewee reported Medicaid was terminated for individuals at booking and/or release. Due to compounded wait times for Medicaid reactivation and a shortage of substance use disorder providers, individuals in this jurisdiction with substance use disorders waited up to 10 weeks post-release to receive an assessment for substance use disorder services. The county jail and local Department of Health and Human Services office in this county collaborated to resolve the wrongful termination with no solution identified at the time of interviews.

Without a reliable system to identify to predict Medicaid suspension status, collaborators struggled to provide consistent reactivation and release support.

Difficult Reactivation Process

Most interviewees reported a similar process for Medicaid reactivation. Generally, this process included the following steps:

| Learn of Suspension: An individual learned of their suspension (either through a pre-release screening or on their own). |

| Reactivation: The DHHS case worker reactivated Medicaid for the individual to receive health care coverage. Most often, individuals were expected to visit their local DHHS office in-person following release with proof of incarceration (retrieved from the jail) paperwork to reactivate their Medicaid. |

| Wait for reactivation: Upon reactivation through DHHS, individuals were still left waiting up to 45 days until reactivation was realized in their Medicaid record. |

Interviewees explained that released individuals faced significant barriers to reactivating their Medicaid including:

![]() Lack of Understanding of Medicaid and How it Can Help

Lack of Understanding of Medicaid and How it Can Help

![]()

Insufficient Transportation to/from DHHS Office

![]() Inaccessible or Lack of "Proof of Incarceration" Paperwork

Inaccessible or Lack of "Proof of Incarceration" Paperwork

![]() Challenges in Navigating Community Agencies

Challenges in Navigating Community Agencies

![]() Lack of Cellphone or Reliable Communication

Lack of Cellphone or Reliable Communication

![]() Unstable or No Address for Formal Communication or Mail

Unstable or No Address for Formal Communication or Mail

![]() Unmet Basic Needs (Such as immediate housing, food, and family needs)

Unmet Basic Needs (Such as immediate housing, food, and family needs)

Many interviewees reported their county jail communicated automatically or manually with MDHHS local offices on individuals' booking in the jail. However, only a few jail administrative interviewees sent reports to MDHHS about an individual's release. Interviewees reported it was unclear how Medicaid is suspended and what informs this suspension. Several interviewees hypothesized suspension is informed by jail booking reports sent to the Social Security Administration.

The barriers and hurdles faced by Michigan's jails to communicate suspension and reactivation information are mirrored in other states. An article published in 2019 by the Kaiser Family Foundation (Wachino & Artiga, 2019) said,

"…creating automated processes to suspend and reinstate coverage is challenging and requires overcoming major technology hurdles and addressing variations in systems and processes across agencies and corrections facilities."

Ineffective Partnerships

Although most interviewees built strong relationships between jail personnel, CMHs, and other community agency staff, some experienced problematic communications and relationships with collaborators. Incongruent belief systems were the most significant cause of an ineffective partnership. For example, one interviewee reported collaboration was difficult if jail employees (specifically correctional officers working directly with incarcerated individuals) did not believe in the Medicaid reactivation or enrollment efforts facilitated within the jail. Interviewees reported jail cooperation in Medicaid reactivation and enrollment efforts was essential to continuity of care.

One interviewee, a CMH employee, expressed that CMH collaborations and innovations created additional burdens on the jail and its staff. Coordinated Medicaid efforts (including enrollment and/or activation) in the jail required increased inmate engagement with CMH or provider staff. Increased inmate engagement necessitated additional jail staff to transport and supervise meetings and additional jail facility space to house meetings. Telecommunicated meetings did not mitigate the need for staffing and facility space and require increased capacity for technology.

Relationships with local DHHS offices varied greatly among interviewees. In some cases, interviewees reported they noted local DHHS workers were unaware of the implications of incarceration on Medicaid coverage, eligibility, and reactivation. Generally, interviewees shared their relationships and level of collaboration with DHHS offices depended on individual employees' cooperation and experience.

Lack of Resources

Many interviewees, both those employed by the jail and by community agencies, expressed a need for additional funding or support to fully implement Medicaid reactivation/improved enrollment practices in jails. Specific needs included:

![]() Personnel: a need for more jail personnel, specifically correctional officers, to provide inmate supervision during coordination meetings, send and receive bookings/release reports, and communicate with community partners on Medicaid issues.

Personnel: a need for more jail personnel, specifically correctional officers, to provide inmate supervision during coordination meetings, send and receive bookings/release reports, and communicate with community partners on Medicaid issues.

Facility: a need for improved or additional space for coordination meetings in the jail, either during an individual's incarceration or during the release process. Space used to coordinate Medicaid benefits must consider privacy, access to jail administrative staff, and security.

Facility: a need for improved or additional space for coordination meetings in the jail, either during an individual's incarceration or during the release process. Space used to coordinate Medicaid benefits must consider privacy, access to jail administrative staff, and security.

![]() Technology: a need for jail-approved technology including computers, access to appropriate health records or benefits records, and access to reliable internet. Interviewees typically gleaned Medicaid information using CMH portals. CMH employees reported they had limited information about individuals never served by CMH or those served by a CMH outside of the county conducting the inquiry.

Technology: a need for jail-approved technology including computers, access to appropriate health records or benefits records, and access to reliable internet. Interviewees typically gleaned Medicaid information using CMH portals. CMH employees reported they had limited information about individuals never served by CMH or those served by a CMH outside of the county conducting the inquiry.

Resource and funding restrictions limited jails and their collaborators in who they could assist or what reactivation, preparation, or enrollment services could be provided. For example, several interviewees provided Medicaid eligibility-related services through grants limited to individuals with substance use disorders, or specific opioid use disorders.

County resources were stretched thin due to the challenge of providing health care to a population with high levels of chronic illness and behavioral health disorders, and the inability to tap into Medicaid coverage.

Unpredictable Release Dates and Times

Consistently, interviewees from jails and CMHs expressed unpredictable release dates as a barrier to reactivating Medicaid. Jails shared that bonds and pre-trial releases made release dates difficult to specify. The COVID-19 pandemic made defining release dates even more difficult to manage as individuals were released early to reduce the spread of the disease. Often, jails worked to manage release protocols and did not have adequate time to inform their community partners of upcoming releases.

Interviewees reported the least challenging release dates to manage are for individuals who have already been convicted and sentenced. Unpredictable release days and short jail stays are a barrier nationally and make coverage coordination difficult (Wachino & Artiga, 2019).

Identified Innovations

Interviewees reported resolving or mitigating barriers with new/strengthened processes that ensured more individuals accessed Medicaid coverage. The four key innovations included

- Comprehensive screening for Medicaid status

- Standard discharge protocol

- Collaboration between partners

- Use of peers

Two interviewees engaged all four of the key innovations. Their efforts created clear and inclusive processes for ensuring individuals leaving jail have access to key services. Many of the recommendations provided later in this report are based on the innovations already practiced in counties across Michigan.

Comprehensive Screening for Medicaid Status/Activation

Jail staff reported conducting a screen for all individuals booked into their jails. However, jails did not report they conducted comprehensive Medicaid screenings. Only two interviewees reported conducting a Medicaid screening on all jailed individuals and verified the information with the CMH or DHHS. Only one jail (Eaton County) conducted Medicaid enrollment activities for all eligible individuals in their jail.

Of the jurisdictions who asked jailed individuals about insurance at screening (8 out of 10), most asked on an "as needed" basis or were not validating information from another source. The booking process was the most common time to gather information on an individual's insurance status.

The below table displays the details of how Medicaid or insurance information was gathered in the 8 counties that collect such information. Counties/Jurisdictions highlighted in blue are those who conducted comprehensive Medicaid screenings.

| Jurisdiction | When | Who | Details | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | As needed | CMH | The CMH conducted a Medicaid screening with individuals served by jail mental health professionals | Urban |

| B | Booking | Jail | Jail staff asked at booking if individuals had insurance but did not verify the information | Rural |

| C | As needed | CMH | The CMH triaged and activated CMH treatment teams for jailed CMH consumers to improve their access care | Urban |

| D | As needed | CMH | The CMH reviewed eligibility and reactivation only with individual who had open CMH cases prior to incarceration | Rural |

| E | Booking/release | CMH | All jailed individuals were reviewed through CMH Medicaid system to ensure they were active or enrolled | Urban |

| F | Booking | Jail | Jail staff asked at booking if individuals had insurance | Urban |

| G | Booking | Jail | Jails ensured qualifying services were covered by Medicaid | Rural |

| H | Booking | Jail & DHHS | Daily booking report was sent to local MDHHS office where screening occurred | Urban |

Some interviewees reported innovative Medicaid screenings where staff (jail, CMH, or DHHS staff) thoroughly screened all individuals booked into the jail. They reported submitting released individuals' names through the CMH electronic health record or by sending a booking report to MDHHS for review. From those screenings, jails and collaborators collected information on an individual's Medicaid status (activated or suspended) and eligibility for the unenrolled. Once the screening was complete, innovative jurisdictions conducted several release activities to support individuals who were confirmed to have suspended Medicaid or were eligible to enroll. These release activities included:

Reactivation of Medicaid through DHHS collaboration

Communication with DHHS to prepare for reactivation efforts

Transportation and housing coordination

Reactivation of other supports including food benefits

Standard Discharge Protocol

In well-developed, collaborative jurisdictions, release dates for sentenced individuals were known to community partners in advance of release, standard release protocols were followed, and individuals had their Medicaid reactivated the day of their release.

Standard release protocols varied among interviewees. Some interviewees prepared the individual for reactivating their own Medicaid upon release. Other interviewees offered comprehensive release activities with the individuals, including scheduling and attending a DHHS reactivation meeting, scheduling and attending a primary care appointment on the day of release, retrieving medications from a pharmacy, and securing housing.

Collaboration Between Partners

Key collaborations created pathways for care continuity and improved the transition from jail back to community. Innovative counties and jurisdictions developed collaborations between jails, CMHs, DHHS, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), and pharmacies.

| Jurisdiction | DHHS Involvement | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| A | Yes- Onsite at CMH | Urban |

| B | No onsite DHHS worker | Rural |

| C | No onsite DHHS worker | Urban |

| D | No onsite DHHS worker | Rural |

| E | Yes- Onsite at CMH | Urban |

| F | No onsite DHHS worker | Urban |

| G | No onsite DHHS worker | Rural |

| H | Yes- Onsite at CMH | Urban |

| I | No onsite DHHS worker | Metro |

| J | No onsite DHHS worker | Metro |

DHHS: Most interviewees, especially CMH interviewees, reported an existing relationship with DHHS (or individual DHHS employees) that improved timeliness of Medicaid reactivation for recently released individuals. Interviewees with the most robust relationships and collaborations often had DHHS onsite either at the jail or the provider site (at a CMH or a FQHC). A third of the interviewees had a DHHS worker onsite at a collaborating CMH. DHHS workers onsite at CMHs were most helpful in reactivating Medicaid onsite.

Although this innovation has reportedly improved Medicaid reactivation and enrollment efforts for individuals who are eligible for CMH services, it does not address reactivation needs for the entire population. Individuals recently released that do not qualify for CMH services are left out of the benefits of increased DHHS collaborations at CMH locations. DHHS collaboration at other sites outside of the CMH system (ex. In the jail) would further refine this innovation.

Jail and CMH: Interviewees with the least-expressed barriers and the most innovative approaches reported strong relationships between jail leadership and CMH leadership. These collaborative interviewees directly changed jail policy (e.g., increased inmate engagement in preparation for release, regular booking/release communications, regular collaboration to improve Medicaid enrollment or reactivation activities) to address barriers to Medicaid continuity of care. Relationships between CMH administrators and jail administrators were critical in innovative communities. Regular communications at an executive or leadership level allowed for open communication, collaborative problem solving, and frank discussions about the limitations of both organizations. The strong relationships between decision-makers at both the CMH and the jail were reflected in "on-the-ground" cooperation between staff members working one-on-one with incarcerated individuals preparing to be released.

Strong and concerted relationships between jails and CMHs improves care continuity. However, the communities that rely solely on CMH relationships to bridge gaps between jail and community leave out an entire population of people who do not qualify for CMH services. Individuals with physical health conditions who do not qualify for CMH services are often left out of conversations of care continuity.3

Recommendations

The recommendations outlined below were developed using the innovations described by interviewees across the state, recommendations of interviewees, and national research on the topic. Although many Medicaid reactivation and enrollment activities were facilitated at the local level, larger system changes would expedite advancement across the state. Where possible, state-level recommendations are provided in each section.

| 1. Expedited Medicaid Reactivation |

|---|

| 2. Improved Enrollment Activites |

| 3. Increased Collaborations |

| 4. Comprehensive Discharge Planning |

| 5. Utilization of Policy Levers |

Considerations for Recommendations

Collaboration: Before implementing recommendations, jail administration, jail health care, and community health care providers must be engaged to understand the nuances and consequences of each recommendation.

Finances: Interviewees had the best intentions of their efforts at the forefront but often mentioned that local budgets and resources limited their pursuit of innovations. Recommendations must consider implementing changes with little to no additional budget impacts on already strained local budgets. Not only will caution for finances prevent jails from stretching their staff further, but it will also encourage collaboration and innovative changes.

Federal Medicaid matching funds are a promising funding source for many recommendations outlined in detail below.

Timeline: The recommendations outlined below range in their ease of implementation. Generally, system changes take more time to fully execute over local changes made in jails. To identify timeline of each recommendation, icons will be used to identify long-term or short-term recommendations.

Long-Term Recommendation

A change that requires more than 12-months to implement and will necessitate communications between many collaborators.

Short-Term Recommendation

A change that can be made within 12-months and be refined over time or incrementally improved.

Recommendation One: Expedited Medicaid Reactivation

Access to Medicaid reactivation upon release from jail is critical to an individual's overall health and likelihood to recidivate (Paradise & Garfield, 2013). Delays in reactivation put the released individual at risk of losing their Medicaid coverage altogether. Below are recommendations to improve the reactivation process:

![]() Community Services

Community Services

Intercept 0

Portal: Create and support a portal or website where existing crisis line provider staff can access eligibility and reactivation information for all individuals. The portal would assist staff in referring individuals to enrollment services or DHHS for reactivation of their Medicaid. This would require collaboration with MDHHS.

![]() Community Corrections

Community Corrections

Intercept 5

Portal: Create and support a portal or website where parole and probation staff can access eligibility and reactivation information for all individuals. This would require collaboration with MDHHS and MDOC.

At the Jail Level

Intercept 2, 3 & 4

![]() Kiosk: Create and support a kiosk (a computer with reliable Wi-Fi that connects to a DHHS portal) at location of release where individuals can access and reactivate their own Medicaid during the release process. According to interviewees, a kiosk should be implemented during the release process instead of as an optional "stop" after release.

Kiosk: Create and support a kiosk (a computer with reliable Wi-Fi that connects to a DHHS portal) at location of release where individuals can access and reactivate their own Medicaid during the release process. According to interviewees, a kiosk should be implemented during the release process instead of as an optional "stop" after release.

![]() Note: The CBHJ, at the time of this report, was using a foundation grant to provide tablets to jails across the state of Michigan, including 8 of the counties interviewed in this report. These tablets are primarily utilized for care coordination and behavioral health services. However, this technology could be a starting point to enrich enrollment and reactivation activities in Michigan jails.

Note: The CBHJ, at the time of this report, was using a foundation grant to provide tablets to jails across the state of Michigan, including 8 of the counties interviewed in this report. These tablets are primarily utilized for care coordination and behavioral health services. However, this technology could be a starting point to enrich enrollment and reactivation activities in Michigan jails.

![]() Staffing: Create and support an in-jail position focused on identifying and addressing reactivation needs for incarcerated individuals. This position could be filled in collaboration with a local FQHC, CMH, or DHHS employee.

Staffing: Create and support an in-jail position focused on identifying and addressing reactivation needs for incarcerated individuals. This position could be filled in collaboration with a local FQHC, CMH, or DHHS employee.

![]() Portal: Create and support a portal or website where jail provider staff can access eligibility and reactivation information for all individuals.

Portal: Create and support a portal or website where jail provider staff can access eligibility and reactivation information for all individuals.

Recommendation One: Expedited Medicaid Reactivation at the State Level

In addition to the number of recommendations at the community services, jail, and community corrections level, the State of Michigan could play a pivotal role in expediting Medicaid reactivation including:

![]() Automatic reactivation whereby Medicaid would automatically reactivate using jail booking and release reports. The state could receive booking and release reports and immediately reactivate the individual's Medicaid information (by changing the PET Code). This solution would alleviate the many responsibilities placed on individuals leaving jail and improve their health as they re-enter their communities. A change at the state level is the most sustainable option for jails, CMHs, and previously incarcerated individuals. This change would likely eliminate the need for the additional recommendations implemented in other levels of the system (CMS, 2020).4

Automatic reactivation whereby Medicaid would automatically reactivate using jail booking and release reports. The state could receive booking and release reports and immediately reactivate the individual's Medicaid information (by changing the PET Code). This solution would alleviate the many responsibilities placed on individuals leaving jail and improve their health as they re-enter their communities. A change at the state level is the most sustainable option for jails, CMHs, and previously incarcerated individuals. This change would likely eliminate the need for the additional recommendations implemented in other levels of the system (CMS, 2020).4

![]() Designated DHHS Coordinator Role in which jails are supported by a DHHS liaison to coordinate jail reactivation services for all jailed individuals. Currently, some jailed individuals have their own DHHS caseworker responsible for several activities. A county jail could have many DHHS caseworkers involved in the reactivation of Medicaid post release. A designated DHHS caseworker responsible for reactivating Medicaid for all released (or soon- to-be-released individuals) would centralize caseworkers' reactivation efforts.

Designated DHHS Coordinator Role in which jails are supported by a DHHS liaison to coordinate jail reactivation services for all jailed individuals. Currently, some jailed individuals have their own DHHS caseworker responsible for several activities. A county jail could have many DHHS caseworkers involved in the reactivation of Medicaid post release. A designated DHHS caseworker responsible for reactivating Medicaid for all released (or soon- to-be-released individuals) would centralize caseworkers' reactivation efforts.

Recommendation Two: Improved Enrollment Activities

Communities must consider developing Medicaid enrollment capacity at other points on the Sequential Intercept Model. Increased enrollment points would relieve pressure on jails and increase the likelihood that more individuals involved in the criminal justice system can access Medicaid.

![]() Community Corrections

Community Corrections

Intercept 5

Eligibility Specialist: In collaboration with the local CMH and DHHS office, enrollment activities should expand into community corrections. With more intercepts fulfilling enrollment activities, individuals are less likely to fall through the cracks.

At the Jail Level

Intercept 2, 3 & 4

![]() Eligibility Specialist: Jails that do not already have an eligibility specialist should seek partnership with their DHHS field office to position one in the jail. This would improve enrollment activities and facilitate collaboration between jails and community resources.

Eligibility Specialist: Jails that do not already have an eligibility specialist should seek partnership with their DHHS field office to position one in the jail. This would improve enrollment activities and facilitate collaboration between jails and community resources.

Recommendation Two: Improved Enrollment Activities at the State Level

The State of Michigan can assist in the facilitation of enrollment activities in jails across the state. The below recommendations would reduce geographical disparities in jail Medicaid enrollment activities and create sustainable funding systems for enrollment efforts.

![]() Develop Legislation to guide Medicaid enrollment practices in jails. Legislation could direct jails to inform MDHHS regarding the incarceration status of eligible individuals. This would put some "teeth" behind any guidelines sent out to jails by MDHHS. Administrative efficiencies leading to state budget savings is the argument for legislating this strategy.

Develop Legislation to guide Medicaid enrollment practices in jails. Legislation could direct jails to inform MDHHS regarding the incarceration status of eligible individuals. This would put some "teeth" behind any guidelines sent out to jails by MDHHS. Administrative efficiencies leading to state budget savings is the argument for legislating this strategy.

![]() Funding Expansion using Medicaid Match funds to help cover jail administrative expenses related to enrollment activities. States can apply for Federal match funds ranging from 50-90% coverage of costs for:

Funding Expansion using Medicaid Match funds to help cover jail administrative expenses related to enrollment activities. States can apply for Federal match funds ranging from 50-90% coverage of costs for:

- Establishing jail information exchanges with the state departments (Plotkin & Blandford, 2017)

- Supporting jail enrollment activities through funding to jail administrations (Jannetta et al., 2017)

Recommendation Three: Increased Collaborations

All innovative interviewees reported well-developed collaborations between jails and community partners. Increased collaboration can prevent individuals from falling through the cracks as they transition from jail back into communities. Collaboration looks different for each community as financial resources and partners vary. Leaders at jails and community organizations can facilitate collaborative efforts through relationship building and discussing common goals.

At All Intercepts

Intercept 1, 2, 3, 4 & 5

![]()

Collaborations between community partners varies in communities based on available resources, existing relationships, and needs of those served. Key partners include DHHS, FQHCs, CMHs, Prepaid Inpatient Health Plans (PIHPs), providers of behavioral health services, primary care providers, Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, local health departments, court systems, and other available community resources.

Engaging partners in Medicaid access can reduce financial burdens on counties, create pathways for care, improve health care access, and reduce recidivism rates. Utilizing existing community resources is a great place for communities to start

Recommendation Four: Comprehensive Discharge Planning

Discharge planning assists individuals leaving jail in preparing for life back in the community. This process, however, is not standardized across the state and can even vary within an individual jail. Improved discharge planning processes would result in comprehensive preparation for individuals returning to communities. Discharge planning should include an insurance component where discharge planners review an individual's Medicaid status/eligibility, next steps for reactivation/enrollment, and connection to health care services in the community.

Discharge Planning

Intercept 0, 3 & 4

![]() Standardized Process: A standard discharge process created in collaboration with jails and community services would improve the health and welfare of individuals released from jail. Collaboration should include multiple collaborators such as FQHCs, CMHs, Medicaid Health Plans, and CCBHCs. Robust standardized discharge planning processes include:

Standardized Process: A standard discharge process created in collaboration with jails and community services would improve the health and welfare of individuals released from jail. Collaboration should include multiple collaborators such as FQHCs, CMHs, Medicaid Health Plans, and CCBHCs. Robust standardized discharge planning processes include:

- Screening of Medicaid activation and eligibility

- Connections to an eligibility specialist

- Referrals to provider of behavioral health or physical health

- Connections to Social Determinants of Health including transportation, housing, and food benefits

Ideally, all individuals released from jail would receive assistance in reactivating their Medicaid. However, because some individuals leave jail under short notice (due to bonding out, results of court proceedings, or other unexpected situations), it is unlikely comprehensive discharge processes could be facilitated with this population.

Recommendation Five: State Policy Levers

![]() MDHHS should use the findings from this report in carrying out Phase II of the ICJIP project, funded by the Michigan Health Endowment Fund. This promising project will provide six jails across the state with access to CareConnect 360 which strives to improve coordination of care for jailed individuals and strengthen their continuity of care upon release. Medicaid enrollment and maintenance of eligibility are key to this project's success. The information contained in this report about existing Medicaid enrollment and eligibility practices in jails will be helpful in mapping out these strategies.

MDHHS should use the findings from this report in carrying out Phase II of the ICJIP project, funded by the Michigan Health Endowment Fund. This promising project will provide six jails across the state with access to CareConnect 360 which strives to improve coordination of care for jailed individuals and strengthen their continuity of care upon release. Medicaid enrollment and maintenance of eligibility are key to this project's success. The information contained in this report about existing Medicaid enrollment and eligibility practices in jails will be helpful in mapping out these strategies.

A second goal of Phase II ICJIP is to "improve Medicaid policy for the justice-involved population". The innovations and recommendations in this report will help shape this state-wide policy.

![]() Amend MDHHS Medicaid Health Plan contracts to include incentives for Medicaid Health Plans to take responsibility for coordination of care activities for their members at release from jail (including Medicaid enrollment) (Nye et al, 2018)5. Provisions in managed care contracts can require Medicaid Health Plans to engage with eligible members while still incarcerated and assign them a care coordinator. From there, a care coordinator could connect them to services as part of re-entry efforts.

Amend MDHHS Medicaid Health Plan contracts to include incentives for Medicaid Health Plans to take responsibility for coordination of care activities for their members at release from jail (including Medicaid enrollment) (Nye et al, 2018)5. Provisions in managed care contracts can require Medicaid Health Plans to engage with eligible members while still incarcerated and assign them a care coordinator. From there, a care coordinator could connect them to services as part of re-entry efforts.

![]() Utilize health home models by incorporating the recently released population into primary care health home, opioid health home, and behavioral health home models (New York Medicaid, 2019)6. In light of Michigan's plans to expand behavioral health and opioid health homes due to their promising outcomes, this could be an opportune time to consider this policy solution. Existing health home eligibility criteria (e.g. individual leaving jail must have opioid use disorder and be at risk of developing another chronic condition) would remain intact, but the referral base would be broadened to include those being released from jails. Given the preponderance of individuals with chronic health conditions and/or serious behavioral health issues among the justice-involved population, a warm handoff to an existing health home where they can receive comprehensive care management, and integrated primary and behavioral health care makes good policy sense.

Utilize health home models by incorporating the recently released population into primary care health home, opioid health home, and behavioral health home models (New York Medicaid, 2019)6. In light of Michigan's plans to expand behavioral health and opioid health homes due to their promising outcomes, this could be an opportune time to consider this policy solution. Existing health home eligibility criteria (e.g. individual leaving jail must have opioid use disorder and be at risk of developing another chronic condition) would remain intact, but the referral base would be broadened to include those being released from jails. Given the preponderance of individuals with chronic health conditions and/or serious behavioral health issues among the justice-involved population, a warm handoff to an existing health home where they can receive comprehensive care management, and integrated primary and behavioral health care makes good policy sense.

![]() Submit an 1115 waiver application to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to authorize federal matching funds for the provision of targeted Medicaid services to eligible justice-involved populations in the 30-day period prior to release. This step would help prevent adverse health outcomes following release. As of 2019, 15 states have initiatives targeting the justice-involved population in approved waivers or waivers pending review. The details of these states' experiences and appropriateness for Michigan should be carefully reviewed (Blewett & Zylla, 2020).

Submit an 1115 waiver application to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to authorize federal matching funds for the provision of targeted Medicaid services to eligible justice-involved populations in the 30-day period prior to release. This step would help prevent adverse health outcomes following release. As of 2019, 15 states have initiatives targeting the justice-involved population in approved waivers or waivers pending review. The details of these states' experiences and appropriateness for Michigan should be carefully reviewed (Blewett & Zylla, 2020).

Conclusion

The research reveals widespread barriers faced by county jails to accessing and reactivating Medicaid for the previously incarcerated population. These barriers are yet another hurdle faced by an already disenfranchised population. It is clear that some counties initiated solutions, thereby improved continuity of care. However, these advancements, in most cases, were temporary workarounds to a larger and more systemic issue of Medicaid access post-release.

The research highlights many short- and long-term community-driven and state-led recommendations. In the short-term, interviewees indicate that a state-wide guideline outlining consistent Medicaid eligibility and enrollment practices would go a long way in reducing some of the reported barriers. These findings may help inform that document and any subsequent training to jail staff.

The most promising long-term solution to address enrollment and reactivation pitfalls is to establish an automatic, centralized IT mechanism with daily feeds to and from the jails that would be triggered when an individual enters and leaves jail. According to CMS guidelines, it is possible that Medicaid matching funds could be used to reduce the economic burden on the state of putting this structure in place. Taken together, these (along with the other recommendations in this report) would go a long way toward creating realistic, sustainable, equitable changes the justice-involved population deserves, while improving health outcomes and reducing recidivism.

References

Blewett, L., Zylla, E. (2020, January). Targeting Justice-Involved Populations through 1115 Medicaid Waiver Initiatives: Implementation experiences of three states. State Health Access Data Assistance Center. https://www.shadac.org/sites/default/files/publications/Justice-involved1115-waiver-initiatives_01.2020.pdf

Bureau of Primary Health Care. (2020). Health Center Program. Health Resources & Services Administration. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/index.html

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020). Eligibility. Medicaid.gov. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/eligibility/index.html

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020, March). Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees (Fiscal Year 2021). US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/PerformanceBudget/FY2021-CJ-Final.pdf

Chase, M., Cox, D., Bryant, B., Holman, L. (2019, March). Federal Policy Impacts on County Jail Inmate Healthcare & Recidivism. National Association of Counties. https://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/documents/Medicaid%20and%20County%20Jails%20Presentation.pdf

Dickinson, L. (2016, August). How and When Medicaid Covers People Under Correctional Supervision. PEW Charitable Trusts. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2016/08/how_and_when_medicaid_covers_people_under_correctional_supervision.pdf

Gates, A., Artiga, S., Rudowitz, R. (2014, September). Health Coverage and Care for the Adult Criminal Justice-Involved Population. The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-care-for-the-adult-criminal-justice-involved-population/

Jannetta, J., Wishner, J.B., Peters, R. (2017, January). Ohio's Medicaid Pre-Release Enrollment Program. Urban Institute, Health Policy Center and Justice Policy Center. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/88051/ohio_medicaid_1.pdf (Page 2)

Medicaid and CHIP (MAC) Learning Collaboratives. (2017, August). Medicaid and Justice-Involved Populations: Strategies to Increase Coverage and Care Coordination. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/mac-learning-collaboratives/justice-involved-populations.pdf

New York Medicaid. (2019, November). Criminal Justice. New York State Department of Health. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/program/medicaid_health_homes/special_populations/criminal_justice.htm

Norris, L. (2020, June). Michigan and the ACA's Medicaid expansion. healthinsurance.org. https://www.healthinsurance.org/michigan-medicaid/

Nye, C., Simon, L., Call, A., Perez-Tineo, C.. (2018, February). Supporting Incarcerated Individuals Transitioning to the Community: State and Health Plan Approaches and Lessons. NORC at the University of Chicago. https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Supporting%20Incarcerated%20Individuals/Healthcare%20for%20Incarcerated%20Individuals.pdf

Paradise, J., Garfield, R. (2013, August). What is Medicaid's Impact on Access to Care, Health Outcomes, and Quality of Care? Setting the Record Straight on the Evidence. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/report-section/what-is-medicaids-impact-on-access-to-care-health-outcomes-and-quality-of-care-setting-the-record-straight-on-the-evidence-issue-brief/

Plotkin, M.R., Blandford, A. (2017, January). Critical Connections: Getting People Leaving Prison and Jail the Mental Health Care and Substance Use Treatment They Need. Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Department of Justice. https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/publications/Critical-Connections-Full-Report.pdf

Wachino, V., Artiga, S. (2019, June). How Connecting Justice-Involved Individuals to Medicaid Can Help Address the Opioid Epidemic. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/how-connecting-justice-involved-individuals-to-medicaid-can-help-address-the-opioid-epidemic/

Willison, J.B., McCoy, E.F., Vasquez-Noriega, C., Reginal, T., Parker, T. (2018, October). Using the Sequential Intercept Model to Guide Local Reform. The Safety and Justice Challenge Innovation Fund. http://www.safetyandjusticechallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018.10.11_Using-the-SIM_finalized.pdf

Zeng, Z. (2019, April). Jail Inmates in 2017. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ji17.pdf

Footnotes

- Youth in secure placements may experience similar barriers to care continuity. This report is focused on adults. ^ Back

- Conducted by Maureen Welch-Marahar and Dr. Debra Pinals with MDHHS in collaboration with the MDOC and the Michigan Sheriffs' Association in late 2019. ^ Back

- The CBHJ focuses on behavioral health innovations. Although the CBHJ acknowledges it is vital to understand the needs of individuals with physical health conditions, it was outside of the scope of this report. ^ Back

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) cover expenses the State incurs in setting up its automated reporting system with the jails. ^ Back

- Many states are engaging Medicaid MCOs in this function, including Ohio, Louisiana, and New Mexico. ^ Back

- In New York state six of its Medicaid health home programs were designed with the needs of the justice involved population in mind. Participants are eligible for health home services upon leaving jail, and they are referred while still incarcerated. ^ Back

For inquiries about this report, please contact:

Joanne Sheldon

JoanneR@TBDSolutions.com

877.823.7348

Remi Romanowski-Pfeiffer

RemiR@TBDSolutions.com

616.228.0764