Jail screening practices and services in response to the opioid risk

October 2023

Our data integration project allowed us to expand our view of who is booked into jail to include more measures of OUD risk, such as prior nonfatal overdose and prior OUD treatment. By doing so, we were able to examine whether our efforts at identifying this high risk subgroup through screening at booking were effective.

When looking at indicators of OUD risk in the community prior to jail booking, we found that 8.2% of our sample of those booked into the jail had OUD treatment evidenced in Medicaid/TEDs billing records during the six months prior to jail booking, including 1.6% receiving MOUD, and that 0.96% had experienced an EMS-attended nonfatal opioid overdose. When looking at the rate of risk identified by the RODS at jail booking, we found 12.94% screened positive for OUD risk.

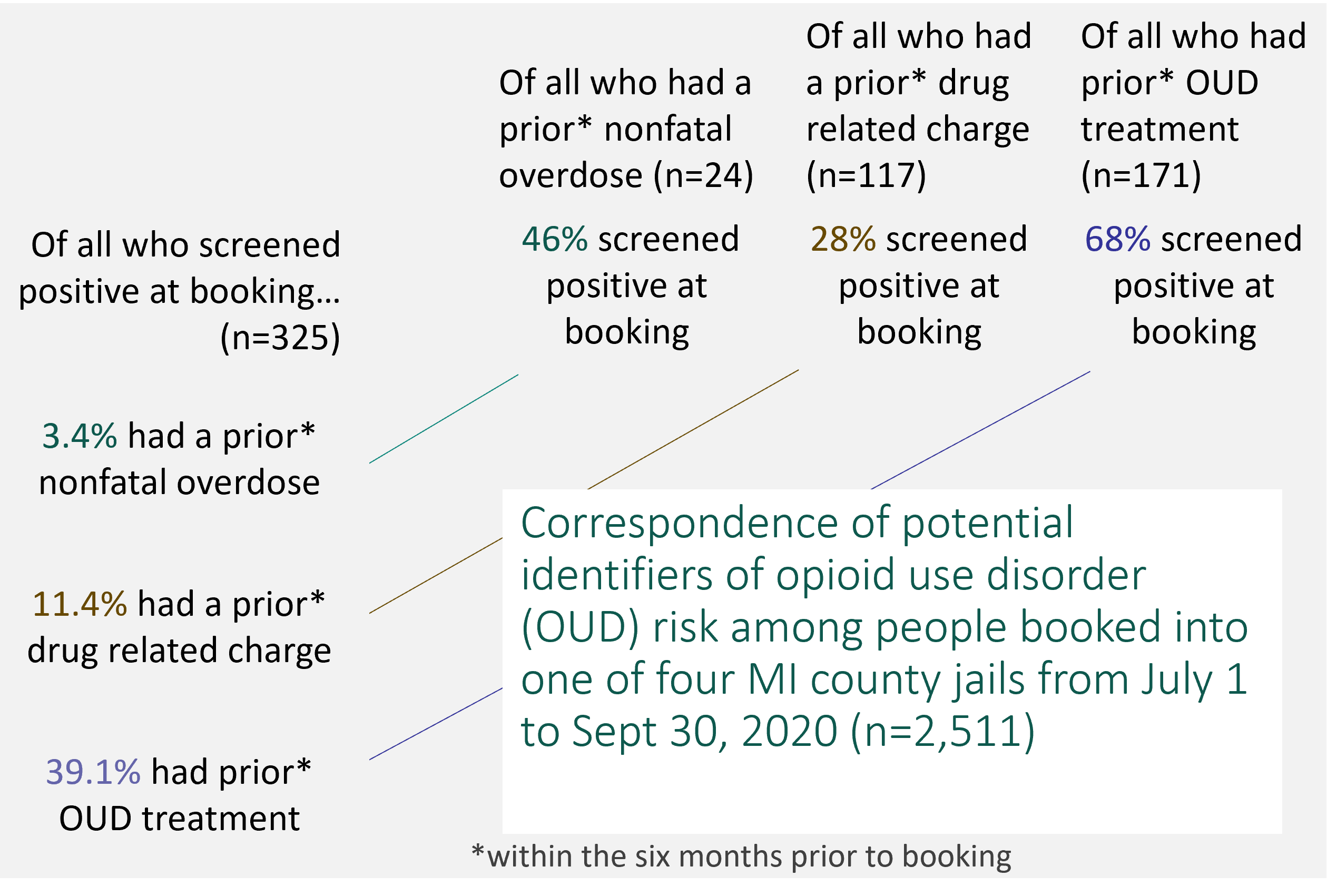

However, when looking at the overlap, that is, whether those receiving treatment or those having had a nonfatal overdose screened positive on the RODS at booking, we recognized some gaps. Of all who had experienced a prior nonfatal overdose, just 46% screened positive at booking on the RODS. Of all with Medicaid or TEDS billing history indicating OUD treatment prior to booking, 68% screened positive on the RODS at booking. The figure summarizes the rate of correspondence between the four potential risk factors examined: Positive RODS screen at booking; prior nonfatal overdose; prior drug-related charge; prior OUD treatment.

However, when looking at the overlap, that is, whether those receiving treatment or those having had a nonfatal overdose screened positive on the RODS at booking, we recognized some gaps. Of all who had experienced a prior nonfatal overdose, just 46% screened positive at booking on the RODS. Of all with Medicaid or TEDS billing history indicating OUD treatment prior to booking, 68% screened positive on the RODS at booking. The figure summarizes the rate of correspondence between the four potential risk factors examined: Positive RODS screen at booking; prior nonfatal overdose; prior drug-related charge; prior OUD treatment.

It may be worthwhile to note that not all individuals screening positive on the RODS for OUD risk should be assumed to need treatment, and a positive screening meant only that a referral to treatment was made. Of our sample, 2.07% ended up receiving MOUD treatment in jail, including 43.9% of those receiving MOUD treatment prior to jail continuing treatment in jail.

As for continuity of care following release, 9.48% of the sample received OUD services within six months following release, including 3.2% receiving MOUD. The average length of time between release and first mental health, substance use disorder, and/or co-occurring disorder service following release was 47 days (range 0-182, std=53.126). As for risk of overdose following release, 0.76% of the sample experienced an EMS-attended opioid overdose within six months, while 0.41% of the sample excluding those from KCCF died from an opioid overdose.

While we were not able to determine a statistically significant association between prior OUD treatment and drug-related mortality, nor between prior EMS-attended nonfatal overdose and drug-related mortality, a relationship was significant between positive RODS and drug-related mortality, with 1.3% overdose fatality among RODS positive responders and 0.3% overdose fatality among those without a RODS-identified risk, X2(1)=4.934, p=0.026. A trend emerges in review of the post period drug-related mortality rates among the sample, as follows:

| Overall (n=1,714) | Positive RODS and NOT enrolled in MOUD in jail (n=195) | Positive RODS (n=238) | No positive RODS (n=1,476) | Enrolled in MOUD in jail (n=43) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-related mortality rate within 6 months following release | 0.4% (n=7) | 1.5% (n=3) | 1.3% (n=3) | 0.3% (n=4) | 0.0% (n=0) |

These EMS naloxone administration data and Medicaid/TEDS treatment billing records suggest that improvement in screening at jail admission may be necessary. Those entering jail may fear being truthful about their past use or if they had ever experienced an overdose. This fear may be related to being charged with an additional offense. However, fear of withdrawal among those actively using may be a counterbalance to such fear. It is also hopeful that data linkage between Medicaid data and jail intake may someday identify past treatment experience to alert jails to the possibility that someone may be actively using opioids or be at risk for withdrawal or subsequent overdose.

Understanding that fatalities attributed to overdose among the recently released population is much higher than community samples, finding methods of identification at critical junctures such as jail intake, is essential to combating mortality rates within the state and one of our continued aims at the CBHJ.